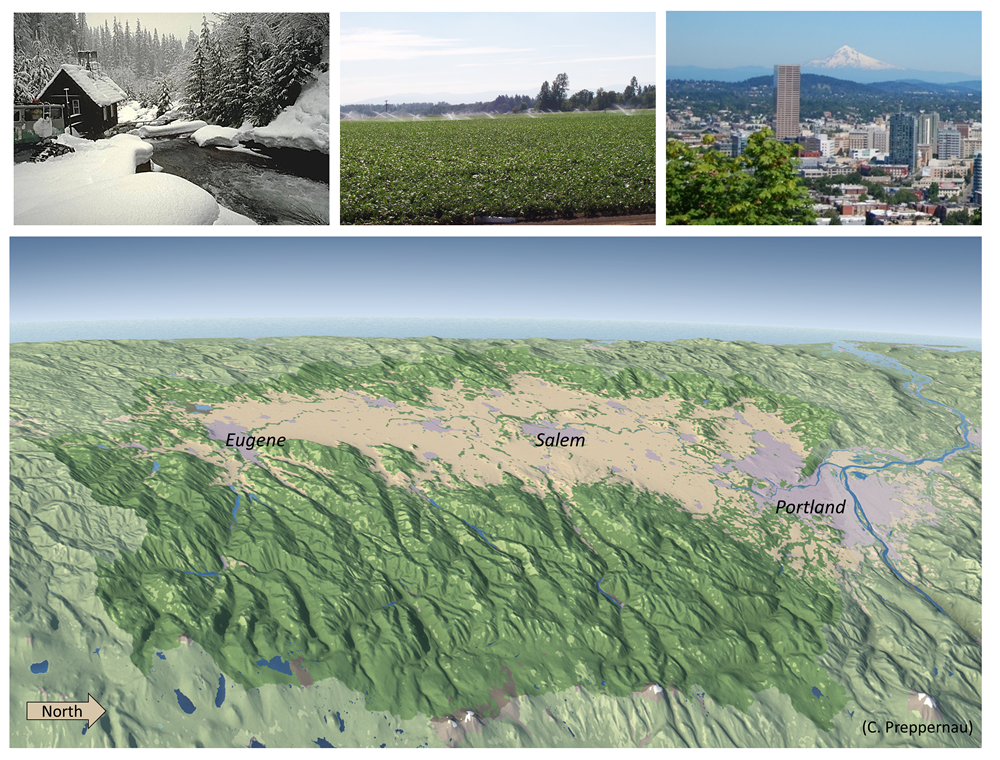

The Willamette River flows north, draining 29,728 square kilometers (11,478 square miles) of diverse landforms and ecology. To the east, High Cascades volcanoes create the basin’s headwaters, with alpine peaks ranging up to 3,426 meters (11,239 feet). To the west, weathered volcanic and sedimentary rocks of the Coast Range bound the basin. Coniferous forests predominate in both mountain ranges and cover about 70% of the basin. Agriculture and city landscapes predominate in the Willamette Valley, with many cities including Eugene, Salem, and Portland clustered along the Willamette River mainstem. The basin’s river systems are home to diverse aquatic species including 36 native fish species, seven of which are listed by the federal or state government as species of concern.

Figure 1. Shaded relief map of the Willamette River Basin, looking to the west and the Pacific Ocean. Image credit: Charles Preppernau, OSU. Photo credits (left to right): Al Levno, OSU, USACE.

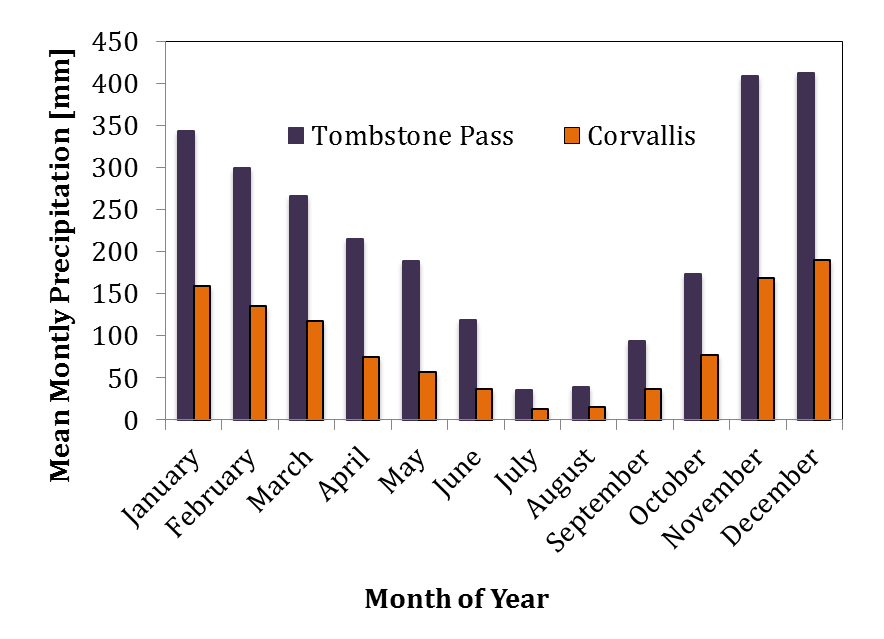

Seasonal patterns strongly influence water supply and demand in the Willamette River Basin. Winters are cool and wet with abundant precipitation that swells the rivers, recharges soil moisture and groundwater, and creates snowpack in the basin’s Cascade mountain headwaters. In contrast, summers are warm and dry, with little precipitation to meet the warm-weather water demands of forests, agriculture, and cities. A system of 13 federal reservoirs managed by the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers (USACE), called the Willamette Project, also exert a strong influence on hydrology by reducing winter flood peaks and augmenting summer flows in the Willamette River mainstem and major tributaries draining the Cascade mountains. The reservoirs were built primarily to reduce flooding in the Willamette Valley, however they also serve other purposes such as power generation, recreation, and water supply for irrigation. Interest in the reservoirs as a water supply source has grown in recent years, and in 2016 the USACE and Oregon Water Resources Department re-initiated a study to consider how stored water is allocated for summer water needs.

Figure 2. Mean monthly precipitation in the Willamette Basin.